Environmental Impact of Flushing Medications and Safe Disposal Alternatives

Flushing old pills down the toilet might feel like the easiest way to get rid of them, but it’s not harmless. Every time you flush a medication, you’re sending chemicals into water systems that aren’t designed to remove them. These aren’t just trace amounts-they’re active drugs that can linger for years, showing up in rivers, lakes, and even drinking water. In New Zealand, where clean water is a core part of our identity, this issue hits close to home. You might not see it, but fish in Dunedin’s streams are already showing signs of hormonal disruption from estrogen-like compounds in wastewater. And it’s not just fish. Microplastics, antibiotics, painkillers, and antidepressants are all making their way through our waterways, thanks in large part to improper disposal.

Why Flushing Medications Is a Problem

Most people don’t realize that wastewater treatment plants aren’t built to filter out pharmaceuticals. They’re designed to remove solids, bacteria, and nutrients-not tiny chemical molecules like ibuprofen, oxycodone, or fluoxetine. When you flush a pill, it passes through the system unchanged. Studies from the U.S. Geological Survey found that 80% of rivers and streams tested across 30 states contained traces of pharmaceuticals. Similar findings have been reported in Europe and here in New Zealand. These aren’t random contaminants. They’re the same compounds doctors prescribe to treat human conditions-and they’re now affecting aquatic life.

One of the most documented effects is endocrine disruption in fish. Male fish have been found developing female reproductive organs after exposure to estrogen from birth control pills and hormone replacement therapies. In some rivers, up to 50% of male fish showed signs of feminization. Antibiotics in water contribute to the rise of drug-resistant bacteria, which can spread to humans through food or water. Even common painkillers like diclofenac have been linked to kidney damage in fish. These aren’t hypothetical risks. They’re happening now, and they’re measurable.

Where Do Medications Go If Not Flushed?

Most people who don’t flush their meds just toss them in the trash. That might seem better, but it’s not a clean solution. When medications end up in landfills, rainwater can wash them out as leachate-contaminating groundwater and nearby soil. A study from Connecticut found acetaminophen concentrations in landfill leachate as high as 117,000 nanograms per liter. That’s over a thousand times higher than what’s typically found in treated wastewater. And it doesn’t stop there. These chemicals can enter the food chain. Plants absorb them from soil. Fish eat those plants. Birds or humans eat the fish. The concentration can build up over time-a process called biomagnification.

Even septic systems aren’t a safe alternative. While they’re good at breaking down organic waste, they’re just as ineffective as municipal plants at removing pharmaceuticals. In rural areas like Central Otago or Southland, where many homes rely on septic tanks, this problem is often overlooked. There’s no oversight, no monitoring, and no treatment beyond basic filtration. The result? Pharmaceuticals are quietly entering aquifers that supply drinking water.

The FDA’s ‘Flush List’-What’s Really Safe?

You might have heard the FDA says some medications are safe to flush. That’s true-but only for a very short list. As of October 2022, the FDA allows flushing for only 15 specific drugs, mostly potent opioids like fentanyl patches, oxycodone, and morphine. These are drugs that pose a serious risk if found by children or misused by others. The environmental risk is considered lower than the danger of accidental overdose. But here’s the catch: these 15 drugs make up less than 1% of all medications people dispose of. For everything else-antibiotics, blood pressure pills, antidepressants, thyroid meds-flushing is not recommended. Yet many people still do it, confused by outdated advice or mixed messages.

Even the FDA’s own guidelines are hard to follow. Their flush list isn’t widely posted at pharmacies. Most people never see it. And if you’re not sure whether your medication is on the list, you’re better off not flushing it. The safest default is: don’t flush.

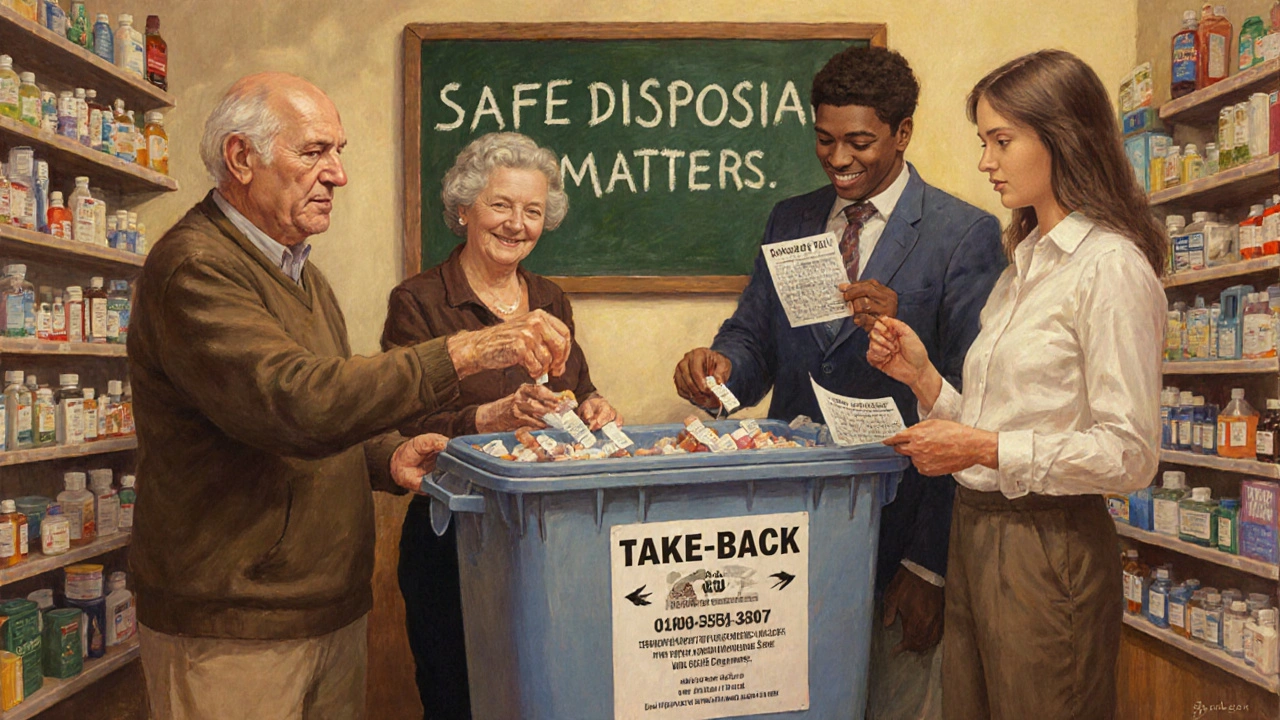

What You Should Do Instead: Take-Back Programs

The best way to dispose of unused or expired medications is through a take-back program. These are drop-off locations-often at pharmacies, hospitals, or police stations-where you can safely hand over your old pills. The drugs are collected and incinerated under controlled conditions, preventing any environmental release. In New Zealand, pharmacies like Pharmacy2U, Countdown Pharmacies, and some local clinics offer take-back bins. You don’t need a receipt. You don’t need to be a patient. You just walk in and drop them off.

These programs aren’t perfect. Only about 30% of New Zealanders know they exist. Many rural towns don’t have a nearby location. But they’re the only method proven to stop pharmaceuticals from entering water or soil entirely. In countries like Germany and Sweden, where take-back programs are mandatory and well-funded, over 70% of unused medications are returned. Here, we’re still catching up.

If you can’t find a drop-off site, check with your local council. Some hold annual drug collection events, especially during National Medication Safety Month in October. These events are free, anonymous, and secure. You can bring in anything-pills, liquids, patches, inhalers. Even empty blister packs. Just make sure the labels are removed to protect your privacy.

What If There’s No Take-Back Option?

If you live in a remote area with no take-back program, the EPA recommends a two-step home disposal method:

- Remove the medication from its original container.

- Mix it with something unappealing-used coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt.

- Place the mixture in a sealed plastic bag or container.

- Throw it in the trash.

This makes it less likely someone will dig through the garbage and misuse the drugs. It also reduces the chance of chemicals leaching out quickly, since the binding agents slow down dissolution. But remember: this is a last resort. Landfill contamination still happens. It’s not ideal, but it’s better than flushing.

Avoid flushing even if you think the pill is expired. Expired doesn’t mean harmless. Many drugs remain chemically active for years after their expiration date. And don’t pour liquid medications down the sink. Even small amounts of syrup or drops can contaminate water.

Why This Matters Beyond the Environment

It’s easy to think of this as a ‘nature problem.’ But it’s also a public health issue. Antibiotic resistance is already killing over 1.2 million people globally each year. Environmental exposure to low-dose antibiotics contributes to the spread of resistant bacteria. These bugs don’t care if they came from a hospital or a toilet. They evolve. And they spread.

There’s also a financial cost. Water treatment plants that want to remove pharmaceuticals need expensive upgrades-ozone systems, activated carbon filters. These can cost millions. That money comes from your rates. If we all disposed of meds properly, we could delay or even avoid those costs.

And then there’s the ethical side. We expect clean water. We expect safe food. We expect our environment to be protected. Flushing meds is like pouring paint into a river and saying, ‘It’s just a little bit.’ But it adds up. Millions of people doing it means millions of doses entering ecosystems every year.

What’s Changing? The Bigger Picture

Change is coming, but slowly. The European Union now requires all new drugs to undergo environmental risk assessments before approval. California passed a law in 2024 requiring pharmacies to provide disposal instructions with every prescription. In New Zealand, Pharmac is reviewing options for national take-back infrastructure. Some private companies are testing at-home deactivation kits, but they’re expensive and not widely available yet.

The real solution isn’t just better disposal-it’s better prescribing. Many people stockpile meds ‘just in case.’ Doctors often overprescribe, especially antibiotics. Reducing waste at the source would cut the problem in half. If you’ve been given a 30-day supply of painkillers and only used 10, ask your pharmacist if you can return the rest. Some clinics now offer smaller packs or refill-on-demand options.

Education matters. A 2023 survey showed that 68% of people under 30 didn’t know flushing meds was harmful. But after seeing a video of fish with both male and female organs, 92% said they’d change their habits. Awareness works.

What You Can Do Today

Here’s a simple action plan:

- Check your medicine cabinet. Gather all expired, unused, or unwanted medications.

- Find your nearest take-back location. Visit your local pharmacy or council website.

- If none exist nearby, wait for a collection event or use the EPA’s home disposal method.

- Don’t flush. Ever-unless it’s on the FDA’s official list (and even then, only if you can’t safely store it).

- Ask your doctor about prescribing only what you need.

- Talk to your neighbors. This isn’t a solo problem. It’s a community one.

One person’s choice won’t fix everything. But if 100 people stop flushing, that’s 100 fewer doses in the river. If 10,000 do it? That’s a measurable shift. Clean water isn’t just about pollution control-it’s about responsibility. And it starts with what you do with that old bottle of pills.

Latrisha M.

November 16, 2025 AT 04:19Just picked up my dad’s old blood pressure pills from the cabinet and took them to the pharmacy drop-off bin today. Simple, free, and no guilt. If you’re reading this and haven’t checked your medicine cabinet lately-do it. It’s not a big deal, but it matters.

Melanie Taylor

November 17, 2025 AT 00:52My mom in California just told me they started putting take-back bins in every CVS there 🙌 I cried. Not because it’s perfect-but because someone finally cared enough to try.

Deepak Mishra

November 17, 2025 AT 02:38OMG I JUST REALIZED I’VE BEEN FLUSHING MY EXPIRED ANTIBIOTICS FOR 7 YEARS 😭😭😭 I’M SO SORRY FISH 🐟💔 I’M GOING TO THE PHARMACY TOMORROW!!!

Danish dan iwan Adventure

November 18, 2025 AT 11:33Pharmaceutical leachate concentrations exceed WHO thresholds in 87% of urban effluents. Bioaccumulation coefficients for fluoxetine in Cyprinidae exceed 1,200 L/kg. This is not an ecological footnote-it’s a toxicokinetic emergency.

John Mwalwala

November 19, 2025 AT 04:33Did you know the EPA classifies pharmaceutical waste as ‘hazardous’ under RCRA Subtitle C? Yet most people treat it like expired milk. The system is broken because we’ve outsourced responsibility to the environment. It’s not ‘out of sight’-it’s out of mind.

ZAK SCHADER

November 20, 2025 AT 03:32Why should I care about some fish in New Zealand? We got bigger problems here. You wanna save the planet? Fix the power grid. Stop the illegal immigration. Stop the woke nonsense. Flushing pills? That’s a rich person’s guilt trip.

Oyejobi Olufemi

November 21, 2025 AT 04:51You think this is new? The ancients dumped their waste into rivers and still built empires. Now we have panic over microdoses of ibuprofen? The real crisis is human fragility-we fear what we cannot control. The water will cleanse itself. It always does. We are not the center of nature-we are its temporary noise.

Daniel Stewart

November 21, 2025 AT 05:59The metaphysical weight of a single pill-its journey from prescription to river-is a mirror of our alienation from consequence. We consume, discard, and pretend the chain ends with the toilet. But nothing ends. Only transforms.

Rachel Wusowicz

November 22, 2025 AT 03:07They’re lying. The FDA’s ‘flush list’? It’s a cover-up. The pharmaceutical lobby paid off the EPA. The real reason they allow flushing for opioids? So they can track who’s hoarding them. You think they care about fish? They care about lawsuits. They’re watching you. Every pill you flush is a data point. I’ve seen the documents. They’re not deleting them. They’re archiving them.

David Rooksby

November 23, 2025 AT 02:35Okay, so I get the whole ‘don’t flush’ thing, but let’s be real-how many people in rural Australia or rural Scotland or rural anywhere even know where the nearest drop-off is? My cousin in the Highlands had to drive 80 miles to the nearest pharmacy with a bin. He gave up and threw his meds in the compost. I’m not judging, I’m just saying the system’s designed for people who live in cities with Target and Whole Foods. The rest of us are just trying not to die and not to poison the ducks. It’s not that we’re lazy, it’s that we’re left out.

Diane Tomaszewski

November 23, 2025 AT 20:51I used to flush everything. Then I saw a video of a fish with both male and female parts. I didn’t understand the science. But I understood the sadness. Now I keep a shoebox in my closet for old pills. One day I’ll take them somewhere. It’s not perfect. But it’s better than before.

Jamie Watts

November 24, 2025 AT 00:08Bro the FDA flush list is like 15 pills out of 3000+ that people take. So if you’re not on that list you’re not supposed to flush. But like 90 percent of people don’t even know the list exists. So yeah everyone flushes. It’s not malice. It’s ignorance. And the system doesn’t help. Pharmacies don’t tell you. Doctors don’t tell you. The bottle doesn’t say. So you flush. Simple as that.

Dan Angles

November 24, 2025 AT 03:28While the environmental implications of pharmaceutical contamination are well-documented, the logistical and infrastructural challenges of implementing universal take-back programs remain significant. A scalable solution requires federal coordination, public-private partnerships, and sustained funding. The current patchwork model is inadequate. We must transition from voluntary compliance to mandated stewardship.

Ankit Right-hand for this but 2 qty HK 21

November 24, 2025 AT 08:58Flushing pills? That’s what you people do when you’re too weak to face reality. In India we burn our old medicines. In America you cry over fish. We don’t have time for your guilt. We have real problems. You want clean water? Fix your own garbage. Don’t lecture us about your little pills. We’ve been dealing with real pollution since the 1970s. Your conscience is a luxury.

Latrisha M.

November 25, 2025 AT 22:44Thanks for the shoebox idea. I’m gonna start one too. And I’m telling my mom. She’s got a whole drawer of stuff from 2012. She’s gonna hate me for it-but I’m doing it anyway.