Why Generic Drugs Are Running Out: The Hidden Crisis in Generic Manufacturing

By 2023, generic drugs made up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. - but they accounted for only about 20% of total drug spending. That sounds like a win: cheap, effective medicine for millions. But behind those numbers is a system on the brink. Essential medications - antibiotics, cancer drugs, heart meds, even basic painkillers like acetaminophen - are vanishing from pharmacy shelves. And it’s not random. It’s structural. The system designed to make generics affordable has broken itself.

How We Got Here

The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to fix a problem: branded drugs were too expensive. It created a fast-track path for generic manufacturers to copy off-patent drugs without repeating costly clinical trials. The result? A booming market for low-cost alternatives. But over time, the incentives flipped. Instead of rewarding reliability, the system started punishing it. Today, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and group purchasing organizations (GPOs) negotiate contracts based on price differences smaller than a tenth of a cent per pill. A manufacturer might win a $10 million contract because they charge $0.001 less per tablet than the next guy. That’s not competition. That’s a race to the bottom. And when the price drops below the cost of making the drug, companies stop making it.The Global Supply Chain Is a Tangled Web

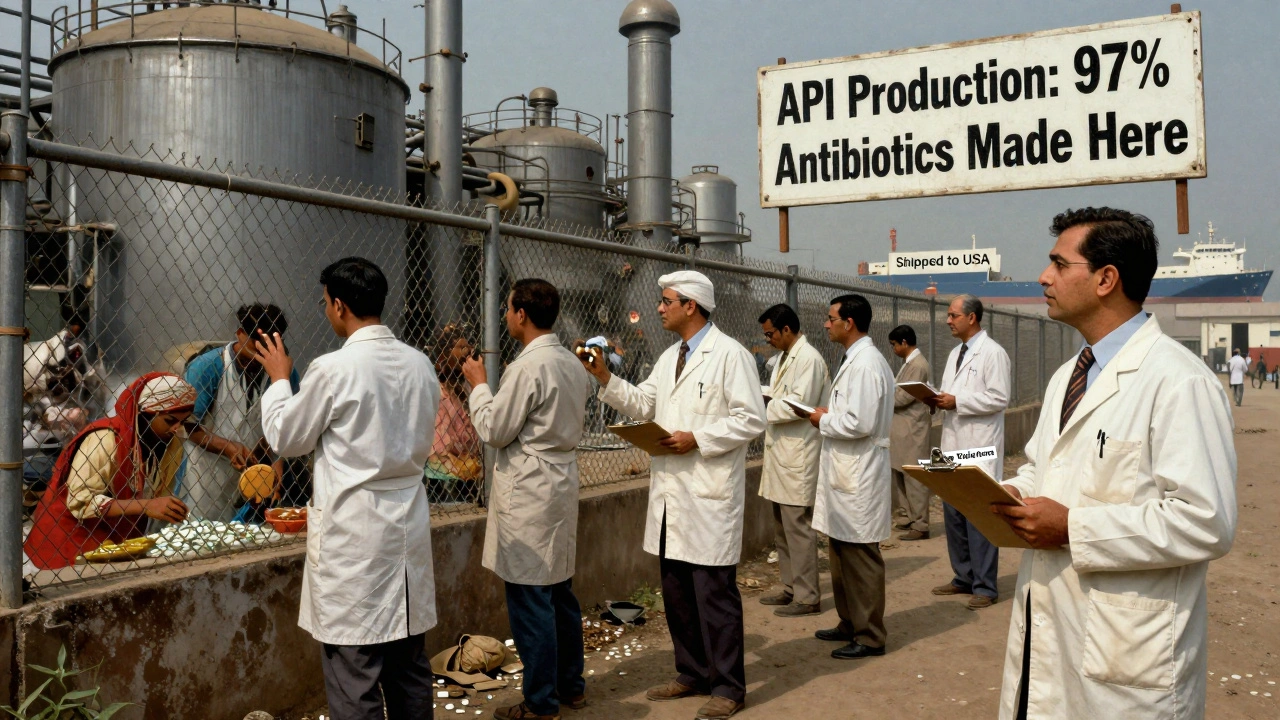

Most people assume their generic pills are made in the U.S. They’re not. As of 2023, 97% of antibiotics, 92% of antivirals, and 83% of the top 100 generic drugs in America rely on active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) made overseas. More than half of all API production happens in India and China. That’s not just a logistics issue - it’s a vulnerability. During the pandemic, when China locked down and India restricted exports of key ingredients, the U.S. felt it immediately. Acetaminophen, the main ingredient in Tylenol and countless generics, saw its precursor material (PAP) drop 80% from Chinese sources. No PAP? No painkillers. No antibiotics? No treatment for common infections. The process doesn’t even happen in one place. An API might be made in India, mixed with fillers in Mexico, coated in Germany, and packaged in the U.S. Each step adds delay, risk, and opportunity for error. And if one link breaks - say, a factory in Gujarat gets shut down by the FDA for quality violations - the whole chain stalls.Quality Control Is a Nightmare

The FDA inspects foreign manufacturing sites, but there aren’t enough inspectors to keep up. In 2022, the FDA found “enormous and systematic quality problems” at Intas Pharmaceuticals in India. Their version of cisplatin, a life-saving cancer drug, was contaminated. It was pulled from shelves. Patients were left without options. A 2023 MedShadow.org study found that generic drugs made in India were linked to 54% more serious adverse events - including hospitalizations and deaths - compared to identical drugs made in the U.S. That doesn’t mean every Indian-made generic is dangerous. But it does mean the margin for error is razor-thin, and oversight is inconsistent. Meanwhile, U.S.-based manufacturers spend $2.3 million on average to fix an FDA Form 483 violation - a list of inspectional deficiencies. It takes 12 to 18 months. Foreign plants? Often they get warnings, then keep operating. The cost of compliance is higher in the U.S. - and the rewards are lower.

Why No One Builds Factories Here Anymore

Building a new FDA-approved drug factory in the U.S. costs between $250 million and $500 million. It takes three to five years. In India or China? $50 million to $100 million. Same output. Half the cost. That’s why the U.S. domestic API manufacturing footprint has shrunk from 35% in 2010 to just 14% in 2023. Even if a company wanted to invest in modern tech - like continuous manufacturing, which improves quality and reduces waste - they can’t afford it. The margins are too thin. One analysis from DrugPatentWatch showed that some generic manufacturers operate at under 5% profit margins. That’s not a business. That’s a charity. And when a company goes under - like Akorn Pharmaceuticals in 2023 - there’s no backup. No safety net. One shutdown, and a drug disappears from the market. No alternatives. No time to ramp up production.The Human Cost

This isn’t theoretical. It’s happening in hospitals, clinics, and living rooms. A hospital pharmacist in Ohio told Reddit users they’d switched antibiotics for 17 different infections in six months because the generics weren’t available. A nurse practitioner in Texas had to monitor 89 patients switching from generic levothyroxine to brand-name versions - a change that requires careful blood tests and adjustments. Patients are paying more, too. One Medicare beneficiary saw their monthly heart medication jump from $10 to $450 when the generic ran out. That’s not a price increase. That’s a financial emergency. The FDA’s drug shortage portal saw complaints rise 327% between 2019 and 2022. Cancer drugs, antibiotics, and epinephrine - the life-saving shot for allergic reactions - were the most reported. These aren’t luxury items. They’re essentials.

Who’s Responsible?

It’s not one person. It’s a system. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) and group purchasing organizations (GPOs) drive prices down to unsustainable levels. They’re not evil - they’re following their mandate: reduce costs. But they’re not factoring in supply risk. The FDA can’t force manufacturers to produce more. They can only ask. Their Drug Shortage Task Force has limited power. In 2024, the Biden administration added $80 million to inspect foreign facilities - a 12% increase. But there are now 40% more foreign sites needing inspection. It’s like sending one firefighter to a city with 100 burning buildings. Congress is trying. Bipartisan bills in 2023 proposed tax breaks for U.S. API production and strategic stockpiles of critical drugs. But those are band-aids. The real fix? Rewiring the entire pricing model.What Could Actually Help

There are solutions - but they require political will, not just goodwill. First, stop awarding contracts based on price alone. Reward reliability. Reward quality. Reward domestic production. A $0.001 difference per pill isn’t worth losing a cancer drug. Second, create a public-private partnership to fund modern manufacturing. Continuous manufacturing systems aren’t just better - they’re more resilient. But they need investment. The FDA’s Emerging Technology Program has approved 12 such facilities since 2019. That’s great. But they make less than 3% of the nation’s generic drugs. Third, build stockpiles. Not just for pandemics - for everyday shortages. If we can keep strategic petroleum reserves, why not strategic reserves of epinephrine, insulin, or antibiotics? Fourth, incentivize U.S. production. Tax credits, low-interest loans, or guaranteed minimum purchase contracts could bring manufacturing back. The cost of rebuilding domestic capacity is high. But the cost of doing nothing? Far higher.The Bottom Line

We’ve created a system that treats life-saving medicine like a commodity - like toilet paper or light bulbs. But medicine isn’t a commodity. It’s a lifeline. The problem isn’t that generics are bad. It’s that the system that makes them cheap has made them fragile. We can’t fix this by asking manufacturers to “try harder.” We need to fix the rules. Right now, 278 drugs are in shortage - 67% of them generic. That’s the highest number since tracking began in 2011. And without structural change, experts predict that number will keep climbing. By 2027, we could lose nearly a third of the companies that make these drugs. The next time you hear a doctor say, “I’m sorry, the generic isn’t available,” don’t assume it’s bad luck. It’s the result of decades of decisions that prioritized price over people.Why are generic drugs running out if they’re so cheap?

They’re cheap because manufacturers operate on razor-thin margins - sometimes under 5%. When the price drops below the cost to produce, companies stop making the drug. There’s no profit, so no incentive. This leads to shutdowns, and with few competitors, shortages follow.

Are generic drugs made in other countries less safe?

Not all of them. But foreign manufacturing sites - especially in India and China - face less consistent FDA oversight. In 2022, the FDA found serious quality issues at Intas Pharmaceuticals, leading to a recall of a critical cancer drug. Studies show U.S.-made generics have fewer serious adverse events than those made overseas, though correlation isn’t causation. The bigger issue is inconsistent standards and delayed inspections.

Why doesn’t the FDA shut down bad manufacturers?

The FDA does shut down facilities - but it’s slow and limited. Inspecting 72% of drug manufacturing sites overseas is impossible with current staffing. Even when violations are found, the process to enforce changes takes 12-18 months. Meanwhile, patients are left without medication. The agency can only ask manufacturers to increase production - they can’t force them.

Can I trust brand-name drugs if generics are scarce?

Yes - if you can afford them. Brand-name drugs often have single manufacturers with stable supply chains, so they rarely run out. But they cost 10 to 50 times more than generics. Many patients can’t pay that. When generics disappear, people either go without or pay out-of-pocket for the brand - which can be financially devastating.

What’s being done to fix this?

Some steps are being taken: tax incentives for U.S. manufacturing, a $80 million boost to FDA foreign inspections, and proposals for strategic drug stockpiles. But these are small compared to the scale of the problem. Experts say without major policy changes - like rewarding quality over price - shortages will keep getting worse.

Will this get better by 2030?

Not without intervention. Experts predict at least 15 major drug shortages per year through 2030 if nothing changes. The number of U.S. generic manufacturers could drop from 127 to 89 by 2027. The market is consolidating, and the remaining players are under extreme pressure. Stability will only come if policymakers stop treating medicine like a commodity and start treating it like a public good.

Eddie Bennett

December 8, 2025 AT 20:32Been a pharmacist for 15 years. Saw this coming. One day you’re stocking 20 different generics for the same drug, next day it’s just you and the empty shelf. No one talks about how PBMs squeeze the life out of these companies. They want the cheapest pill, no matter if it’s made in a garage in Gujarat. We’re not talking about aspirin here - we’re talking about chemo drugs that vanish overnight.

Courtney Blake

December 9, 2025 AT 17:01Of course it’s happening. We outsourced everything to save a few cents. Now we can’t even get antibiotics when grandma gets pneumonia. China and India don’t give a damn about our kids. If we want medicine, we need to make it here - or stop pretending we’re a sovereign nation. Build the factories. Tax the foreign profiteers. Stop being soft.

Lisa Stringfellow

December 10, 2025 AT 05:47Ugh. I knew this was gonna be one of those posts where someone tries to make me feel bad for wanting cheap meds. Look, I’m on SSDI. I can’t afford brand-name insulin. If the generic disappears, I die. So don’t lecture me about ‘national security’ while you sip your $8 oat milk latte.

Kristi Pope

December 11, 2025 AT 14:34There’s hope. I’ve seen small U.S. labs start making critical generics with FDA support - just not at scale. We need to fund them. Not punish them. And patients? We can write to our reps. Join advocacy groups. This isn’t hopeless - it’s just ignored. Let’s not give up on each other yet 🤍

Aman deep

December 11, 2025 AT 22:21As someone from India, I see this daily. Many factories here are doing their best - but they’re stuck between FDA demands and crazy price pressure. We’re not villains. We’re workers trying to survive too. Maybe instead of blaming, we build bridges? Better inspections, fair pricing, real partnerships. It’s possible. I’ve seen it.

Paul Dixon

December 13, 2025 AT 03:51My dad had a heart attack last year. The generic he needed? Gone. Switched to brand - cost $450/month. Insurance covered $440. I paid $10. That’s not a system. That’s a joke. And yeah, I know it’s complicated - but someone’s gotta say it: this ain’t right.

Vivian Amadi

December 14, 2025 AT 15:08Stop pretending this is about ‘fair pricing.’ It’s corruption. PBMs are middlemen who take 20% of every prescription and then act surprised when factories shut down. They’re the problem. Fire them. Ban their contracts. Done.

Sylvia Frenzel

December 15, 2025 AT 10:13And yet we still let Walmart and CVS negotiate drug prices. They’re not healthcare providers. They’re retail giants. If they want to sell groceries, fine. But they don’t get to decide who lives or dies because they want to cut a dime off a pill.

Jimmy Kärnfeldt

December 16, 2025 AT 07:37Medicine isn’t a commodity. It’s a covenant - between patient and healer, between society and its most vulnerable. We’ve turned it into a spreadsheet. We’ve forgotten that behind every shortage is a person waiting, trembling, wondering if tomorrow’s dose will come. We can do better. We have to. Because if we don’t fix this, we’ve already lost more than pills - we’ve lost our humanity.