Affirmative Consent Laws: How Patient Permission for Medical Substitution Actually Works

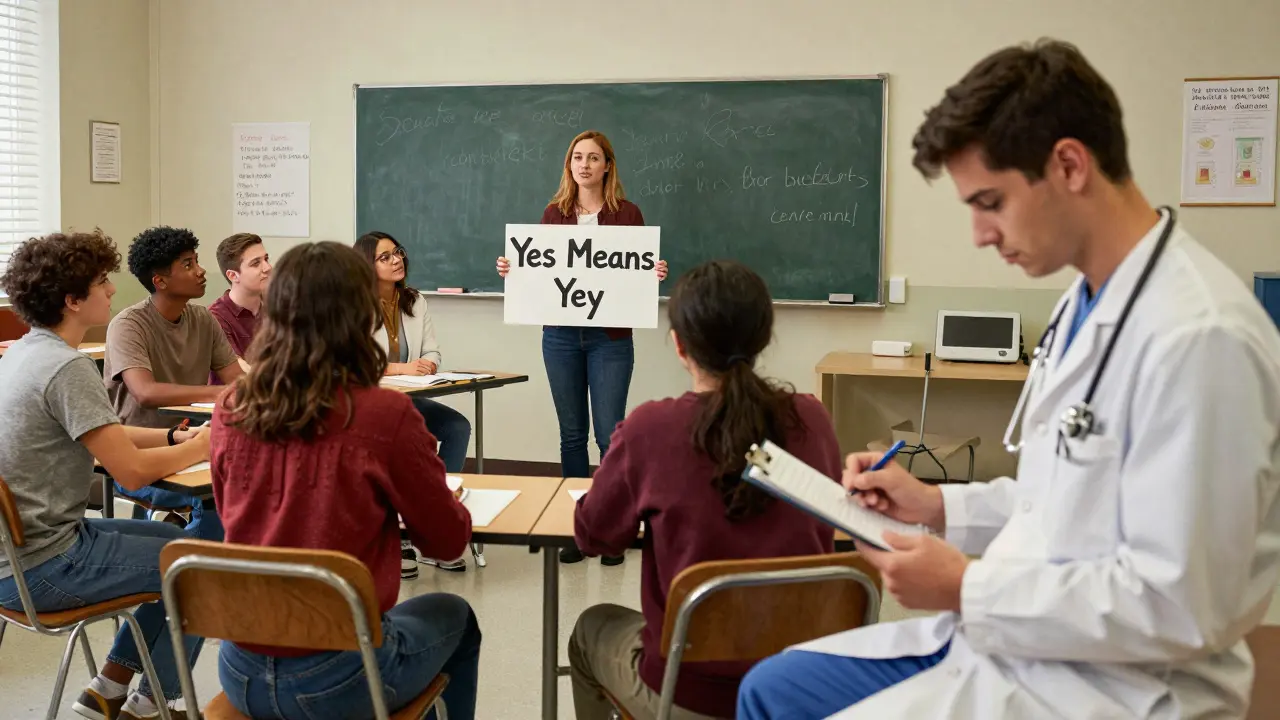

There’s a big mix-up going on. If you’ve heard the term affirmative consent in relation to medical care, you’re not alone-but you’re also wrong. Affirmative consent laws don’t apply to doctors, hospitals, or patient substitutions. They were never meant to. These laws were created to define what counts as legal sexual consent, especially on college campuses and in cases of assault. They say ‘yes means yes’-active, ongoing, voluntary agreement. But when it comes to medical decisions, especially when a patient can’t speak for themselves, the rules are completely different.

What Affirmative Consent Really Means

Affirmative consent laws started appearing in U.S. states around 2014, mostly after the #MeToo movement pushed for clearer standards around sexual activity. California’s Senate Bill 967, which took effect in 2015, was one of the first. It requires that consent for sexual activity be “affirmative, conscious, and voluntary.” That means silence isn’t consent. Passing out isn’t consent. Being pressured isn’t consent. Consent has to be clear, ongoing, and can be pulled at any time.This standard is used in campus disciplinary hearings, criminal cases involving sexual assault, and training programs for students and staff. It’s not a medical rule. It’s not a hospital policy. It’s a legal framework designed to protect people from sexual violence-not to govern who can sign a surgery form.

Medical Consent Has Its Own Rules

When a patient needs treatment, doctors don’t ask for “affirmative consent” the way a partner might. They follow informed consent. That’s a legal and ethical standard that’s been around for over a century. It started with a 1914 court case, Schloendorff v. Society of New York Hospital, where a patient was operated on without permission. The court ruled: every person has the right to decide what happens to their body.Today, informed consent means the doctor must tell the patient:

- What the diagnosis is

- What the treatment involves

- What the risks and benefits are

- What other options exist

- What happens if they say no

- Whether they’re capable of understanding all this

The patient doesn’t have to say “yes” out loud every five minutes. They just need to understand the information and agree-verbally, in writing, or sometimes just by showing up for the procedure. That’s it.

What Happens When a Patient Can’t Consent?

Now, what if the patient is unconscious? Too confused? Too young? That’s where the confusion with “affirmative consent” really kicks in. People assume if someone can’t say “yes,” someone else has to say it for them. That’s true-but it’s not called affirmative consent. It’s called substituted judgment or best interest standard.In California, the Health and Safety Code says that if a patient lacks capacity, a legally authorized person-like a spouse, adult child, or court-appointed guardian-must make the decision. But here’s the key: they don’t decide what they would want. They decide what the patient would have wanted, based on what they know about the patient’s values, beliefs, and past statements.

For example: If a 72-year-old man who never wanted to be hooked up to machines says he’d rather die than live on a ventilator, and he’s now in a coma, his wife can’t say, “I think he’d want to try everything.” She has to say, “He told me he didn’t want to be kept alive by machines.” That’s substituted judgment.

If there’s no record of what the patient would have wanted, then the surrogate uses the “best interest” standard. That means choosing the option that gives the patient the best chance of recovery, least pain, and most dignity. But again-no one is asking for an ongoing “yes” like in a sexual encounter. No one is checking for enthusiastic nodding.

Why People Get This Wrong

It’s not your fault. The language overlaps. “Consent” is used in both settings. Universities run training sessions on affirmative consent for students and also have medical services on campus. Students see both, hear the same word, and assume they’re the same thing.At the University of Colorado Denver, a 2023 survey found 78% of undergrads couldn’t tell the difference between sexual affirmative consent and medical consent. That’s a problem. It leads to confusion when families are making life-or-death decisions. It leads to doctors being asked to explain “why we don’t need a verbal yes every time.”

Even medical students get tangled up. On Reddit’s r/medschool, a top-rated comment from January 2023 said: “Affirmative consent is for sexual activity policies on campus; medical consent uses different standards based on patient capacity and disclosure requirements.” That comment got over 1,200 upvotes. The students know. The system just hasn’t caught up.

What the Law Actually Says

In 2023, the California Supreme Court made this crystal clear in Doe v. Smith. The court ruled: “Affirmative consent standards apply exclusively to sexual misconduct determinations under Title IX and Education Code provisions, not to medical consent scenarios.”The Federation of State Medical Boards issued a similar advisory in March 2023: “Physicians should not apply sexual consent standards to medical decision-making processes.” Why? Because it would slow down emergency care. It would confuse families. It would create legal chaos.

The American Medical Association’s 2023 guidelines reinforce this: “Applying affirmative consent models to medical care creates unnecessary barriers to urgent treatment and misunderstands the legal foundations of medical consent.”

Real-World Examples

Let’s say a 16-year-old girl comes into the ER after a car crash. She’s unconscious. Her parents aren’t there. Can the doctor wait for affirmative consent? No. The doctor acts under emergency exception rules-saving life and limb takes priority.Now, let’s say that same girl had an advance directive saying she didn’t want blood transfusions because of her religious beliefs. The doctor has to honor that. No “yes” needed. No verbal confirmation. Just the document.

Or consider a 12-year-old in New Zealand who needs treatment for an STI. Under New Zealand law, minors can consent to sexual health services without parental permission. That’s not affirmative consent-it’s statutory capacity. The law recognizes that some people, even if young, can make certain medical decisions on their own.

What You Should Do

If you’re a patient: Write down your wishes. Name someone you trust to speak for you if you can’t. Fill out an advance healthcare directive. Talk to your family about what you’d want. Don’t assume they’ll guess right.If you’re a family member: Don’t assume you know what the patient would want. Look for clues. Did they say they didn’t want to be a burden? Did they refuse a treatment in the past? Did they sign a living will? Use those as your guide-not your own fears or hopes.

If you’re a healthcare worker: Don’t confuse the two. Train your staff on the difference. Post clear signs in waiting rooms: “Informed Consent for Treatment ≠ Affirmative Consent for Sexual Activity.” Clarify this early. Save everyone the stress.

Bottom Line

Affirmative consent laws are about preventing sexual violence. They’re not about medical care. Medical consent is about autonomy, understanding, and respect. Substituted judgment is about honoring a person’s voice-even when they can’t speak. Mixing them up doesn’t make things safer. It makes them harder.There’s no such thing as “affirmative consent for medical substitution.” That phrase doesn’t exist in any law, policy, or ethical guideline. It’s a myth. And the sooner we stop repeating it, the better decisions patients and families will make.

Emma Hooper

December 30, 2025 AT 19:43Okay but can we talk about how wild it is that people think doctors need to ask for a verbal ‘yes’ every time they poke someone? 😅 Like, I had a broken wrist last year and the ER doc just handed me a clipboard. I signed it. Done. No enthusiastic nodding. No ‘are you sure?’ every 30 seconds. Medical consent isn’t a Tinder date, it’s a legal form with a pen.

And honestly? The fact that this confusion even exists is kinda scary. People are making life-or-death calls for loved ones and now they’re second-guessing because they heard ‘affirmative consent’ on a campus seminar. We need signs. Like, actual signs in waiting rooms. ‘THIS IS NOT A CONSENSUAL DANCE.’

Harriet Hollingsworth

January 1, 2026 AT 00:56This is why society is falling apart. You can’t just mix up words like that and expect people to behave. Consent is consent. If you’re not saying ‘yes’ clearly and repeatedly, you’re not consenting. Period. The fact that hospitals are getting away with silent agreement is terrifying. What’s next? Letting doctors operate on comatose people because they ‘seemed okay with it’? No. We need the same standard everywhere. No exceptions. No loopholes. No ‘best interest’ nonsense. If they can’t say yes, they don’t get treated. End of story.

Chandreson Chandreas

January 2, 2026 AT 14:03Man, this is such a beautiful breakdown 🙏

It’s like people heard the word ‘consent’ and thought it was some universal magic spell-say it once, and it protects you from everything. But nah. Consent in bed? Different universe than consent in the OR.

One’s about autonomy in intimacy. The other’s about autonomy in vulnerability. Both matter. Both deserve respect. But they’re not twins. They’re cousins who grew up in different cities.

And honestly? The fact that med students are getting this wrong tells me we’re teaching ethics like it’s a buzzword, not a practice. We need more clarity. Less jargon. More humanity.

Also, if you’re reading this and haven’t filled out an advance directive? Do it. Your family will thank you. And so will your future unconscious self 😊

Branden Temew

January 3, 2026 AT 00:44So let me get this straight-according to the AMA, applying sexual consent laws to medicine would ‘create legal chaos’… but we’re fine with applying corporate HR policies to mental health screenings? 🤔

It’s hilarious how we’ll scream about ‘one standard for all’ when it’s about sex, but suddenly ‘context matters’ when it’s about saving a life. Why is it that when a woman says no to sex, we need a signed affidavit and a witness, but when a man’s unconscious and his wife says ‘he’d want everything done,’ we call it ‘substituted judgment’ and move on?

Either consent is sacred or it’s a bureaucratic formality. Pick one. Don’t make it a choose-your-own-adventure based on whether the body is bleeding or blushing.

Hanna Spittel

January 3, 2026 AT 09:38THIS IS A GOVERNMENT TRAP. 🚨

They made up ‘affirmative consent’ to control college students. Now they’re using the same word to sneak in euthanasia by proxy. You think they want families making decisions? NO. They want the state deciding who lives and who dies. Advance directives? That’s the first step to ‘no one’s allowed to live past 70 unless approved.’

Watch. Next year, hospitals will start requiring ‘consent video logs’ for every procedure. ‘Say ‘yes’ clearly, wave your hand, blink twice.’

They’re normalizing surveillance under the guise of ‘safety.’

Don’t sign anything. Don’t trust the system. They’re playing you.

anggit marga

January 4, 2026 AT 20:54Why are Americans so obsessed with copying every stupid law from California? We in Nigeria have been doing medical consent right for decades. You go to the hospital, you sign, you get treated. If you die, you die. No drama. No campus seminars. No ‘enthusiastic nodding.’ You think your grandma in Enugu waits for a 10-minute consent lecture before her hip replacement? Nah. She trusts the doctor. That’s culture. That’s respect. Not this over-legalized American circus.

Stop exporting your confusion. We don’t need it.

Joy Nickles

January 6, 2026 AT 19:24Okay but like… what if the family member who’s making the decision… is a total narcissist?? Like what if the wife says ‘he’d want everything done’ but he actually hated hospitals and told her 17 times he didn’t want to be hooked up to tubes?? And then she’s like ‘I just can’t let him go’ and the hospital goes along with it because they don’t want to get sued??

And then the patient dies in pain and the family blames the doctor??

And the doctor has to go to therapy??

And then the hospital starts requiring ‘consent affidavits notarized by a priest and a dog’??

WHY IS THIS EVEN A THING??

I’m not even mad. I’m just… disappointed. Like… we’re this close to turning healthcare into a courtroom drama with a side of trauma.

Martin Viau

January 7, 2026 AT 13:11It’s a classic case of institutional homonymy collapse. The term ‘consent’ is semantically overloaded across domains with divergent epistemic frameworks-sexual agency versus bodily autonomy in clinical contexts. The conflation stems from lexical redundancy in public discourse, exacerbated by the institutional co-location of sexual education and healthcare services on university campuses.

Moreover, the cognitive load required to disambiguate these constructs exceeds the average health literacy threshold, particularly among populations with limited exposure to legal medicine. The AMA’s position is technically correct but pragmatically insufficient. We need a new lexical marker for medical consent-perhaps ‘informed authorization’-to disentangle the conceptual noise.

Until then, we’re just shouting into the semantic void.

Marilyn Ferrera

January 9, 2026 AT 08:33So many people don’t realize: medical consent isn’t about getting a ‘yes.’ It’s about making sure the person *understands* what they’re saying yes to.

That’s why we have forms, disclosures, and waiting periods. Not because we’re suspicious. Because we care.

If you’re worried about someone making a decision for you? Write it down. Talk to your family. Don’t leave it to guesswork.

And if you’re a provider? Stop using the word ‘affirmative’ near medical forms. Just say ‘informed consent.’ Simple. Clear. Done.

Deepika D

January 9, 2026 AT 11:59Let me tell you something-I’m a nurse in Delhi, and I’ve seen this exact confusion play out a hundred times. Families come in crying, saying ‘But the college told us we need affirmative consent!’ and we have to sit them down and explain, gently, that no, honey, your mom doesn’t need to say ‘yes’ every time the IV is changed.

It’s heartbreaking. They’re scared. They’ve been told that if they don’t demand constant verbal agreement, they’re being negligent. But here’s the truth: the real negligence is not preparing your loved ones in advance. Not writing down your wishes. Not naming your person.

So if you’re reading this, and you’re healthy, and you’re alive-do this one thing today. Sit with your mom, your dad, your sibling. Ask them: ‘If I can’t speak, what do you think I’d want?’ Then write it down. Not a legal document. Just a note. A promise. A whisper between you and them.

That’s real consent. Not a form. Not a law. A relationship.

And if you’re a student? Stop memorizing buzzwords. Start listening to people.

Bennett Ryynanen

January 9, 2026 AT 13:11Bro. This whole thing is a mess because we treat medicine like a courtroom and consent like a TikTok challenge. You want to know what real consent looks like? It’s your grandma holding your hand in the ER and saying ‘I know you’d hate this, but I’m not letting you go.’

It’s not about legal jargon. It’s about love. It’s about knowing someone so well that you can speak for them without a script.

Stop overcomplicating it. Write your damn advance directive. Talk to your people. And if someone tries to tell you you need ‘enthusiastic nodding’ for a CT scan? Laugh in their face. Then go home and hug your mom.

That’s the only consent that matters.